Swallow-tailed Kite: Species Account

Recommended Citation: Coulson, J. O. (August 17, 2013). Species account for Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus. Orleans Audubon Society Technical Bulletin No. 1, Pearl River, Louisiana. Last updated March 5, 2021. Retrieved from URL https://jjaudubon.net/swallow-tailed-kite-project/.

Species Account for Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus

The Swallow-tailed Kite’s beauty and grace are unrivaled among birds. In spring and summer, birders from across the globe travel to its favorite haunts such as the Atchafalaya Basin and Honey Island Swamp to catch a glimpse of this marvelous raptor.

A genetic investigation into the phylogeography of the species found a divergence between the northern and southern subspecies that was broad enough to consider these two distinct species (Washburn 2007).

What is a Kite?

Kites are species of raptors in the Order Accipitriformes whose flight patterns are reminiscent of a paper kite. Kites spend a lot of time on the wing. They are incredibly buoyant and do not need to flap their wings often. “Kite” is not a taxonomic term, as many of the kites are not close relatives.

Phylogenetic Relationships

The Swallow-tailed Kite belongs to the Order Accipitriformes and the Family Accipitridae (hawks, eagles, hawk-eagles, harriers, buzzards, kites, and Old World vultures). Several groups of raptors within the Family Accipitridae that are not close relatives are referred to as kites. One of the kite groups is the pernine kites. This group lacks the bony shield above the eye that is present in most diurnal raptors (Ridgway 1875, Peters 1931). Members of this group specialize in hunting insects and some specialize in feeding on bee and/or wasp larvae. The pernine kites (8 genera, 16 species) consist mostly tropical, Old World species. Both Old and New World representatives include the following: bazas and cuckoo-hawks (Aviceda), Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides), hook-billed kites (Chondrohierax), honey-buzzards (Henicopernis and Pernis), Gray-headed Kite and White-collared Kite (Leptodon), Black-breasted Kite (Hamirostra), and Square-tailed Kite (Lophoictinia; Lerner and Mindell 2005, Griffiths et al 2007). The pernine kites are basal to other Accipitridae except for Elanus and Gampsonyx (Griffiths et al. 2007). Note that the Mississippi Kite, Ictinia mississippiensis, which is somewhat of an ecological correlate to the Swallow-tailed Kite, is not a close relative.

Identification

Adults: The Swallow-tailed Kite has long, pointed wings and a long, deeply forked tail. The crow-sized body is smaller than what might be expected from the bird’s majestic, four-foot wingspan. Kites only weigh about 400 grams or 0.9 pound. The head, neck, abdomen, and legs are white. The dorsal surface of the wing is black above, at the shoulder, and blue-black below. The tail is also black. The underside of the wing is white above and black below. Adult plumage is achieved at approximately one year of age. Irides are usually dark brown.

Juveniles: Juvenile kites differ in appearance in several aspects. Nestlings and recently fledged young usually have a buff to rust-colored wash over the white parts of the plumage. The rusty wash is probably due to porphyrins and pheomelanins (Negro et al. 2009). Feathers on the crown and nape may have dark brown or black shafts. Fresh flight feathers (primaries, secondaries, tertiaries, and some upper wing coverts, as well as the rectrices may be edged in white. The tail is noticeably forked, but it is shorter than that of the adult.

Kites that are molting particularly heavily during June and July tend to be juveniles hatched the previous year that are molting into adult plumage.

Similar Species

The Magnificent Frigatebird, a seabird, has a similar silhouette, but it is larger, and it is not usually found inland. The Mississippi Kite is often mistaken for the Swallow-tailed Kite but it is smaller, grayer, and has a square tail.

Subspecies

Elanoides forficatus forficatus breeds in the southeastern U.S.

Elanoides forficatus yetapa breeds in portions of southern Mexico and in Central and South America.

Breeding Range (in progress)

The current stronghold of the northern Swallow-tailed Kite’s breeding range is in Florida. Breeding sub-populations have also been documented for Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas (Meyer 1995, Coulson et al. 2008, Lockwood and Freeman 2004). Isolated nests have been reported recently, beginning in 2002, near the White River, Arkansas (Chiavacci et al. 2011), and along the Cape Fear River, Bladen County, North Carolina (1 nest in 2013, Carpenter and Allen 2013).

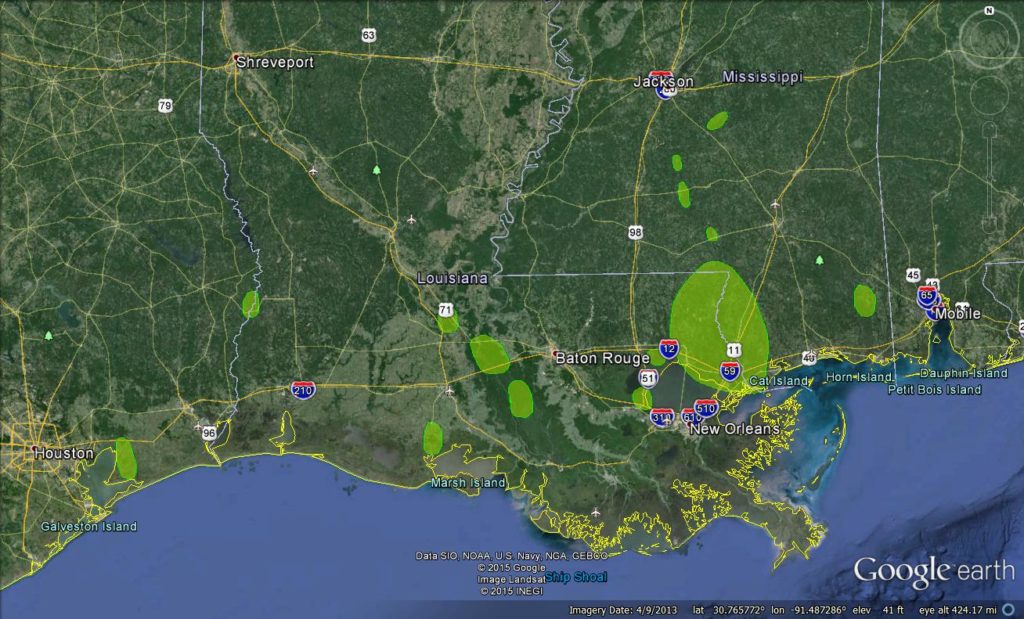

Figure 1. Breeding sub-populations of Swallow-tailed Kite in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi, documented by Orleans Audubon Society (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data). Confirmed nesting areas indicated by green polygons.

Habitat (in progress)

Breeding populations are often associated with large, swamp-river basins. The swamps and bottomland hardwood forests of the Pearl River Basin, Louisiana and Mississippi, provide prime nesting habitats.

Diet

Diet

Few diet studies have been conducted. Meyer et al. (2004) studied food deliveries at eight nests in southern Florida and identified 1092 prey items. The biomass consisted of chiefly vertebrate prey (97%) of the following composition: 56% frogs, 30% birds, and 11% reptiles (N = 1092). Gerhardt et al. (2004) studied food deliveries at five nests in northern Guatemala during the nestling phase and identified 1496 prey items. The frequency of prey items was 62% insects, 18% nestling birds, and 10% reptiles and amphibians. Fruit (0.3%) was also delivered to nestlings.

Foraging Behaviors

Swallow-tailed Kites sometimes grasp, dislodge and carry passerine nests containing nestlings to their own nests (Skutch 1965, Coulson 2002). Skutch (1965) observed E. f. yetapa robbing and carrying a Golden-hooded Tanager nest in Costa Rica. In the U.S., Coulson (2002, J. Coulson, unpubl. data) recovered the following species’ nests in and beneath E. f. forficatus nests and roosts: Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Northern Parula, Hooded Warbler, Wood Thrush, Red-eyed Vireo, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, and Acadian Flycatcher. Apparently small bird nests provide an efficient means of transporting food, and once the contents are eaten, kites sometimes incorporate the nest into their own nest (Coulson 2002).

Nesting Habits

In the southeastern U.S., the Swallow-tailed Kite’s breeding season begins around March 15 and extends through July 31, although most young have fledged by July 15th.

Kites place their nests unusually high up in a tree–typically in the upper tenth. The nest tree seems to be selected more for its crown shape rather than the tree species. What the kite wants is to be able to launch itself off from the nest and fully extend its long wings to take flight. Trees used for nesting usually have an open crown structure, and often with a spiky top. In bottomland hardwood forests, kites often build their nests in sweetgum, Eastern or swamp cottonwood, baldcypress or water tupelo. In pine forests, a dominant pine is usually selected for the nest tree.

The nest itself is barely larger than a dinner plate and it is often flat on top or even convex rather than having a concave nest cup. The nest is a stick basket adorned with curtains of Spanish moss trailing down off of the sides. The light green fruticose lichens are also used and may tail down the sides of the nest. A lot of the sticks used in building the nest are lichen-covered (scale lichens and fruticose lichens).

Vocalizations

The juvenile food-begging cries are very high-pitched and whistle-like: wheee-wheee-whee or eeee-eeee-eeee.

Adult vocalizations include a kee-kee-kee or klee-klee-klee call that is given in several contexts. A breeding adult often make this call after it has delivered food or nest material to the nest and is launching off from the nest platform to take flight and depart.

Predators

In a breeding season study in Louisiana and Mississippi, 65 predation events were detected during the monitoring of 317 nesting attempts (1997–2006) and 103 radio-tagged kites (90 fledglings, 13 breeding adults; Coulson et al. 2008). Predation-related mortality (108–116 depredated kites and eggs) was caused primarily by raptors: 46.0–46.7% by Great Horned Owl, 1.7–1.8% by Barred Owl, 0.9% by a Red-shouldered or Broad-winged Hawk, and 44.9–45.3% by unidentified raptors. Climbing predators were responsible for the remaining predation: 5.1–6.1% by North American rat snakes, and 0.9% by raccoon. Great Horned Owl was not only the most frequently documented predator, but also the only predator known to kill adults (Coulson et al. 2008). In 2009, in Pearl River, LA, a Red-tailed Hawk was observed carrying a Swallow-tailed Kite nestling in its talons (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data).

In Guatemala, Brown Jay, Keel-billed Toucan and spider monkeys depredated eggs and young (Gerhardt et al. 2012).

Siblicide was obligate at nests containing two young in a population at Tikal National Park, Guatemala (Gerhardt et al. 1997). Siblicide has been documented in Louisiana and Mississippi subpopulations but this behavior is uncommon here (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data).

Parasites

Endoparasites: In a Louisiana and Mississippi study, 60 live and 5 salvaged kites were screened for gastrointestinal parasites (Coulson et al. 2010). Kites hosted the following helminths (nematodes: Dispharynx sp., Procyrnea sp., and an immature ascarid; trematodes: Order Strigeatida; cestodes: Taenia vexata; acanthocephalan: Centrorhynchus spinosus), and two taxa of protozoans (Phylum Sporozoa: unidentified coccidia; and Phylum Metamonada: Giardia sp.). Two of 43 nestlings examined during banding hosted larval Protocalliphora sp. (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Helminth prevalence was 27.7%, with trematodes and nematodes being most prevalent, 13.8% and 10.8% respectively (N = 65). The prevalence of Dispharynx sp. in first-year kites was 11.5% (N = 52). Dispharynx sp. caused stomach lesions in two first-year kites (Coulson et al. 2010).

Ectoparasites: A new species of feather mite. Aetacarus elanoides sp. N. (Acari: Gabuciniidae), was described from Swallow-tailed Kite (Proctor et al. 2006).

In Guatemala, botfly infestations were common in nestlings and caused at least one death (Gerhardt et al. 2012).

Longevity

Data on longevity for this species are scant. One kite was captured alive at 7 years, 51 days of age (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data). Details are as follows: a male Swallow-tailed Kite from a nest near the town of Pearl River, St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, hatched on 5 May 2002 (+/- 2 d) and was banded and radio-tagged as a nestling on 2 June 2002. He was recaptured as a breeding adult on 25 June 2009, 2.87 km from his natal origin.

Communal Roosting Habits

One aspect of the species’ social behavior is communal roosting. Swallow-tailed Kites often gather together in groups to roost (perch in trees) together overnight. During the breeding season within a nesting neighborhood, communal roosts usually contain from 2 to 30 kites, often composed of both breeders and non-breeders. In mid to late July through early August, Swallow-tailed Kites often gather in larger pre-migration communal roosts that may be associated with waterways, especially Gulf and Atlantic coastal rivers, and the floodplains of peninsular Florida. Several very large pre-migration roosts, sometimes containing several thousand kites, are being monitored by our partners at the Avian Research and Conservation Institute.

One aspect of the species’ social behavior is communal roosting. Swallow-tailed Kites often gather together in groups to roost (perch in trees) together overnight. During the breeding season within a nesting neighborhood, communal roosts usually contain from 2 to 30 kites, often composed of both breeders and non-breeders. In mid to late July through early August, Swallow-tailed Kites often gather in larger pre-migration communal roosts that may be associated with waterways, especially Gulf and Atlantic coastal rivers, and the floodplains of peninsular Florida. Several very large pre-migration roosts, sometimes containing several thousand kites, are being monitored by our partners at the Avian Research and Conservation Institute.

Migration (in progress)

Wintering Grounds (in progress)

Interspecific Interactions

A pair of Swallow-tailed Kites used a Mississippi Kite nest from the previous year (Cely 1987), and Mississippi Kites have used inactive, failed Swallow-tailed Kite nests (Coulson 2002). Swallow-tailed Kites fairly frequently build their nests on top old Fish Crow nests, in some cases with little augmentation (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data). In 2016, I documented one instance of a Red-tailed Hawk augmenting and using a Swallow-tailed Kite nest from the previous year (J. O. Coulson, unpubl. data).

Anatomy

The lores have dense feathering which is thought to be adaptive, protecting the kite from wasp stings. The species may be something of a wasp specialist, grasping wasp nests on the wing and out-flying the guards to eat the larvae.

Literature Cited

Carpenter, J. P. and D. H. Allen. 2013. First nest record of Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus) in North Carolina. Chat 77:74-78.

Cely, J. E. 1987. American Swallow-tailed Kite uses Mississippi Kite nest. Journal of Raptor Research 21:124.

Chiavacci, S. J., T. J. Bader, A. M. St. Pierre, J. C. Bednarz, and K. L. Rowe. 2011. Reproductive Status of Swallow-Tailed Kites in East-Central Arkansas. Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 123:97-101.

Coulson, J. O. 2001. Swallow-tailed Kites carry passerine nests containing nestlings to their own nests. Wilson Bulletin 113:340–342. Download the .pdf file here: PDF

Coulson, J. O. 2002. Mississippi Kites use Swallow-tailed Kite nests. Journal of Raptor Research 36:155–156. Download the .pdf file here: PDF

Coulson, J. O., T. D. Coulson, S. A. DeFrancesch, and T. W. Sherry. 2008. Predators of the Swallow-tailed Kite in southern Louisiana and Mississippi. Journal of Raptor Research 42:1–12. Download the .pdf file here: PDF

Coulson, J. O., S. J. Taft and T. D. Coulson. 2010. Gastrointestinal parasites of the Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus), including a report of lesions associated with the nematode Dispharynx sp. Journal of Raptor Research 44:208–214. Download the .pdf file here: PDF

Gerhardt, R. P., M. A. Vasquez, and D. M. Gerhardt. 1997. Siblicide in Swallow-tailed Kites. Wilson Bulletin 109:112–120.

Gerhardt, R. P., D. M. Gerhardt, and M. A. Vasquez. 2004. Food deliveries to nests of Swallow-tailed Kites in Tikal National Park, Guatemala. Condor 106:177–181.

Gerhardt, R. P., D. M. Gerhardt, and M. A. Vasquez. 2012. Swallow-tailed Kite. Pages 60–67 in Neotropical Birds of Prey. D. F. Whitacre, ed. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, and Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Griffiths, C. S., G. F. Barrowclough, J. G., Groth, and L. A. Mertz. 2007. Phylogeny, diversity, and classification of the Accipitridae based on DNA sequences of the RAG-1 exon. J. Avian Biology. 38:587-602.

Lerner, H. R. L. and D. P. Mindell 2005. Phylogeny of eagles, Old World vultures, and other Accipitridae based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 37:327-346.

Lockwood, M. W. and B. Freeman 2004. The TOS handbook of Texas birds. Texas A&M University Press, College Station.

Meyer, K. D., S. M. McGehee, and M. W. Collopy. 2004. Food deliveries at Swallow-tailed Kite nests in southern Florida. Condor 106:171–176.

Negro J. J., G. R. Bortolotti, R. Mateo, and I. M. García. 2009. Porphyrins and pheomelanins contribute to the reddish juvenal plumage of black-shouldered kites. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 153:296-299.

Peters, J.L. 1931. Check-list of Birds of the World. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Proctor, H., G. M. Zimmerman, and K. D. Meyer. 2006. A new feather mite, Aetacarus elanoides sp. N. (Acari: Gabuciniidae) from the Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus) (Linnaeus) (Falconiformes: Accipitridae: Perninae). Journal of Zootaxa 1252:37-47.

Ridgway, R. 1875. Outlines of a Natural Arrangement of the Falconidae. Dept. of the Interior, Washington, Govt. Printing Office, June 10, 1875. Extracted from Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, No. 4, Second Series.

Skutch, A. F. 1965. Life history notes of two tropical American kites. Condor 67:235–246.

Washburn, A. 2007. Phylogeography of the Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus). Master’s Thesis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Birds of North America Species Account:

Meyer, K. D. 1995. Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus). No. 138 in A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. The birds of North America. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.